|

| Image c/o Nasa http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/msl/multimedia/pia16068.html |

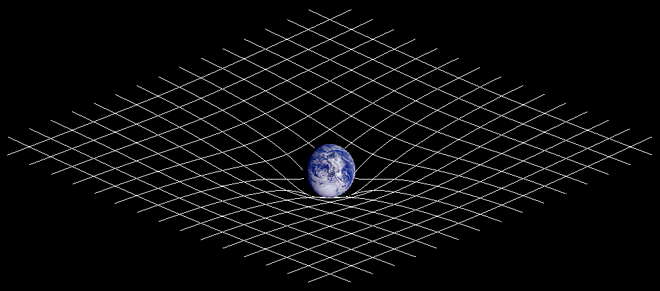

The technological triumph is astonishing. A payload weighing almost a ton was sent over 560 million kilometers through space, exposed to astonishing levels of radiation, hitting the Martian atmosphere at 20,000km/h, reaching temperatures of 2,000C, decelerating and then deploying a parachute, dropping its heat-shield, and then being lowered by the built-in “skycrane” to the surface, just over 2km from it’s target.

Consider just one illustration of that achievement. Landing 2.4km away from it’s target after a trip of over half a billion kilometers is a bit like hitting the bulls-eye on the dartboard in my house just outside Gaborone with a dart you threw from Dar-Es-Salaam.

The explorer is now motoring around the Martian surface, taking pictures, examining rocks and soil and sending the results back home to Earth. It’s a genuine triumph of science, and its often overlooked cousin, engineering.

One thing that charmed me about the mission is it the name they gave to this explorer: “Curiosity”. The name was actually given to it by a 12-year old girl who won a competition to name the explorer. Her essay included the wonderful phrase “curiosity is the passion that drives us through our everyday lives.” I agree entirely. Curiosity is surely a sign of intelligence. It’s by no means a purely human virtue, plenty of other animals are curious, but humanity has been able to take curiosity to the highest level. Curiosity combined with science and engineering has led to automated explorers on Mars, the Moon landings, the extinction of smallpox, anti-retroviral drugs and to people living longer and happier lives today than they have ever done in the past. Curiosity has propelled humanity to its current heights, just like rockets propelled Curiosity to Mars.

The problem is that curiosity has an enemy: established thought.

There’s a proverb you may have heard. “Curiosity killed the cat”. It’s used whenever someone thinks that someone else, someone cleverer than them, is being overly curious, a bit too enquiring, someone who is asking to many questions.

The problem with the phrase it what it suggests: that curiosity is somehow dangerous. That asking questions leads to trouble. That having an enquiring mind is a bad thing.

As well as hearing this from parents tired of questions from their irritating children you also encounter the same reaction from any person or group who don’t want to be questioned. Unfortunately this happens an awful lot within religious belief systems. They have a dogma, a set of core beliefs that members are often simply forbidden from questioning. They’re certainly forbidden from getting a logical answer. Questions undermine the authority and power of the leadership. No religion is immune to this and neither are certain political belief systems. Unfortunately for the people of many countries in the past, and quite a few today, questioning things is not permitted. Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Syria, North Korea and a host of countries ending in “-istan” haven’t permitted open questioning of authority. People have died for doing so.

All of these groups have portrayed curiosity as something wrong, something anti-social, something to be stamped out by burning the curious at the stake, imprisoning them or forbidding them from speaking and writing. The problem is that all countries that opposed curiosity eventually collapsed either due to failed economies, war losses or popular uprising. Their leaders failed to understand that oppressing curiosity is a recipe for disaster. What it means for supernatural belief systems is another matter.

Meanwhile those of us who approve of humanity’s desire to question and explore can sit back, delighted that they show themselves in magnificent feats of exploration, scientific progress and prosperity. The opponents of curiosity only have extinction to look forward to.